Beijing Bastard Read online

Page 22

Then one day I realized that I could either wish he were a different cat, or I could accept him just as he was. And I saw that while he watched my every move, like other family members I’d lived with, he passed no judgment. One neurasthenic female per household was probably enough. To accept him fully was revolutionary. Eventually, he began to sit quietly in my lap while I typed, and when I came home late at night, he ran joyfully to the door to greet me.

Chapter Twenty-two

Facts Are Facts

My phone rang.

“Hello?”

“Haluo’r?”

I knew the voice on the other end of the phone. Laichun. The Incomprehensible Clown again. The clown character in Peking Opera, I had learned, is the only opera role that can break out of history, allude to current events, and speak in colloquialisms.

He laughed and said in Chinese, “Miss Wang?”

“Oh, hi.” I switched into Chinese too. At least he had stopped calling me Reporter Wang.

“This Tuesday is my mother’s birthday. We want you to come celebrate with us.”

“Is there a party?”

“No, come whenever you like.”

Laichun’s voice filled me with dread. I meant no thanks but I said okay. Why did I go back? Filmmaking ambition, partly, but something more powerful. I returned to a guilt-tripping family to whom I would never measure up like spent blood returns to the heart.

It turned out that there was a party, a lunch that I was going to miss because I came in the early afternoon. I brought an ostentatious bouquet of flowers. Overcooked vegetables and slices of meat floated in the cooled soup of the hotpot. Without the unifying distraction of eating, the usual mob of family members sat around limply.

“Welcome, welcome!” said Laichun, leaping up.

I gave the grandmother the flowers.

“What a big bunch of flowers,” she said wearily, perhaps dreading the disruption that I inflicted. Sometimes she seemed like the only sane one among them. “How much did they cost?”

“You can’t ask that! She’s a foreigner!” said Laisheng. He let out a satisfied burp.

“Miss Wang!” roared the grandfather, and then fell silent. The grandmother poured a cup of tea and fed spoonfuls of it to him. I turned on my camera.

“Do you know why there are no bathrooms among the 9,999 rooms in the Forbidden City?” the eldest brother with the half-paralyzed face demanded of me.

“No,” I said.

He didn’t tell me. He told me instead about a style of Peking Opera that was developed by sword-wielding bodyguards who had worked during the reign of the Empress Dowager Cixi. After losing their jobs when guns were introduced at the end of the Qing Dynasty, they went down south and started a kind of dance that eventually became added to Peking Opera. I nodded eagerly, excited for a Peking Opera story that wasn’t long-winded and incomprehensible. The grandfather began snoring. We looked over at him and laughed.

The two brothers carried on a conversation about me right before my eyes, as usual.

“She’s not a reporter anymore, is she? She counts as a friend of ours,” said Laichun in a strangely lugubrious voice. “I don’t understand.”

“She just likes to hear old stories,” said Laisheng.

Laichun turned to me morosely and said, “Don’t bother explaining. It’s better this way.”

The clock chimed three o’clock. The grandfather let out an animal sound in the background. The older brother said, “Emperor Yongzheng died in the bathroom of the palace, so after him, the imperial palace didn’t have a bathroom anymore. It’s just that simple.”

The grandfather woke up and immediately challenged me to name all the gates of the ancient city wall. I couldn’t. He snorted in derision and began a slow trip about the inner wall naming the nine gates. I didn’t mention to him that he had named Qianmen twice and forgotten Andingmen. He then recited all seven of the outer gates. I listened as patiently as I could without the heart to remind him that the old city wall had been demolished almost fifty years before.

Laichun looked at me significantly. “I don’t even know what to say to you.”

“What do you normally talk about with one another?” I asked. “Why not talk about that?”

The family started leaving. Laisheng left to go to the theater. He checked with me to make sure he had the English pronunciation of ten yuan right. His job that night was to stand outside the theater dressed up as the Monkey King and to ask foreign tourists if they wanted to have their picture taken with him for a fee of ten yuan.

Laichun sat on a small single bed on the far side of the room. I sat next to him. Here was my chance to capture the family’s quieter, more intimate moments. Greenish afternoon light slanted in. I pointed the camera at him and he began talking about the beauty of sculpture.

“China has urban sculptures now. There’s one in Qingdao called The Wind of May,” he said, his description conjuring up the image of an enormous red metal soft-serve ice cream. “You should go and see it. Right now it’s—”

“March.”

“It’s almost May. Imagine the wind in May and then go see this sculpture. It’ll be good for you.”

“Maybe I’ll wait until May to go,” I said.

“From an artistic perspective, I think about it this way,” he said, a secretive, knowing look passing over his face. “Wind.”

“Wind?”

“Wind.” He stared off into space. The grandmother fussed with the birdcages before going into the other room for a nap. When he started speaking again, it was slowly. “Miss Wang, you should come more often.”

“I’d like to.”

“You only come when I call you.”

“That’s not true.”

“I told you already, we’re friends, right?”

“Right.”

“I’ve told you more than once: I don’t want to take shortcuts. Facts are facts. People make things into things they’re not. I’m just a performer.”

“What?” His voice was heavy with portent and I didn’t like the turn this conversation was taking.

“What was your impression of me the first time you met me?”

“The first time?”

“It was on a screen.”

I dimly recalled seeing a scratchy video recording of someone’s Peking Opera performance. “Oh, I think I remember. But nothing too clearly.” I turned the camera away from him and pointed it at a washbasin across the room still containing a dirty washcloth from the morning, as if to shield my eyes from the car wreck that seemed to be unfolding in slow motion.

“But what were your impressions?”

“I told you I didn’t have any impression. Why do you keep asking?”

He let out a laugh. “‘I didn’t have any impression.’ That’s good. I had an impression of you. I became damaged.”

“Damaged?”

“My impression of you damaged me. You forced your way into my mind and I became spoiled.”

“Excuse me?”

“Sometimes I wonder—where has she gone?” he mused. “Didn’t she say she was coming over? My mind has problems. What should I do about this?”

“I don’t know.”

“Don’t you think I’m damaged?”

“No, I think maybe you don’t meet many new people.”

“Maybe you are like a painting that has entered my mind.”

“Maybe.”

“I always wonder where she is. My heart has settled into this position. This is not good. Is this good?”

“This?” I wondered how I had missed the signs. The repeated phone calls. The alarming levels of enthusiasm at my visits. The crashing disappointment at my departures. His face with the clown mask he’d been in too much of a hurry to take off.

He laughed again, acid and sad. “This is your res

ponse? This is not good.” He got up and left the room, slamming the door behind him.

I sat there alone, the video camera still running. His confession made me ill. With it, he had yanked me over the final threshold into their family’s most interior room, where my self receded to the point of terror and I became, if only for an imagined moment, part of their family. Sometimes friends become so close that you treat them like family. Had he truly imagined I would become his blushing bride? Or was the opposite true—had the clown used me, in that same moment, to break out of family and out of history? He must have felt suffocated by his family too, and my life of floating around must have looked enticing. An escape. I shut off the video camera.

I tiptoed past the sleeping grandfather, back through the lightless rooms and the skinny restaurant, and out onto the anonymous, forgiving street.

• • •

I called Yang Lina to tell her what had happened and she burst into laughter that surprised and irritated me.

“That is so great,” she said. “He fell in love with you?”

“Yes. It wasn’t great. It was horrible,” I said. Why had I been expecting her sympathy? “I can never go back.”

“You have to go back!” she shrieked. “That’s a great story.”

“That’s the end of the story,” I said firmly. “I’m not going back.”

“You had no idea the whole time?”

“I had no idea.”

“You are too adorable!”

Over the next few weeks, I spent a lot of time at home brooding over what had gone wrong. Yang Lina was right. I had been hopelessly naïve. How had I not seen it coming? Why had I thought I could just squat in the Zhangs’ lair, shoot some footage, and emerge unscathed?

Part Five

Chapter Twenty-three

The Marzipan Inquirer

Despite, or maybe because of, the spectacular implosion of my documentary, I had a golden summer. I lived the life of a hunzi, working only as much as I needed to and going out dancing every weekend. I felt as if I had all the time in the world. The tapes stayed safely tucked away at the back of a drawer.

The Brits were much better at championing the lack of ambition and better at being colonials than us Americans, and I spent many afternoons with them drinking cucumber-soaked Pimm’s while pedal-boating around Houhai and Qianhai, the lakes in the center of Beijing. There was always an underground art exhibition to go to or a new bar opening. On the banks of Houhai, a small bar opened. Sparsely furnished with rattan furniture and huge-leafed plants, it didn’t have a sign or even a name; everyone called it the No Name Bar. Out the window was Old Beijing—grandpas fishing or swimming in the lake, grannies sauntering by in super slo-mo. It was the romantic old image I’d had of China come to life and I began spending a lot of time there.

But the city in the summer was humid and heavily polluted, so Cookie and I often escaped to the countryside. One time we took a bus to a temple west of the city to people-watch. Another time when an old friend visited, the three of us hiked up a crumbling section of the Great Wall and slept out on a parapet. We broke up a sign asking in English for an outrageous entrance fee and used it for kindling. Rising up from the darkness of a village below were the sounds of men talking and laughing as they drank. In the morning we followed the ruins of the wall along the ridge of the mountain until we reached the next village, which happened to have a small but functioning go-kart track. It was bathetic, like my life.

One day that summer as I was walking in my neighborhood, I glanced down the length of my street and I noticed that the tops of the tall trees lining the street touched and intertwined, creating a vaulted roof. In the sunlight, the leaves glowed a rich shade of green I’d never seen before in Beijing, and golden shards of light fell onto the cars and people speeding obliviously underneath. Locking eyes with the perfect tunnel of gold and green, I caught my breath. My god, my street is beautiful, I thought. But I never saw it like that again.

Cookie’s father visited from India. She had always seemed like such an eccentric creature but we saw that she was a carbon copy of her dad: Both were gin-swilling foreign correspondents, both idiosyncratic, both like caricatures of themselves. They even had the same slightly bowlegged walk. He took in our neighborhood, Maizidian’r, with an amused eye and dubbed it Marzipan Street.

His visit coincided with the event of the summer: the rave on the Great Wall. We rode chartered tour buses up north of the city and climbed up a section of the wall to find our DJ friends in an open-air watchtower with their turntables going. House music thumped out over the mountains, and as we danced the night air was clear and cool on our skins. I had never felt more like an invading barbarian, or more giddy. Cookie’s dad stood observing us for an article he was going to write for Time, and when it got late, he went to sleep in a nearby guesthouse. We danced and drank until the sun peeked over the snaking line of the Great Wall, which hugged the ridge of a mountain as far as the eye could see.

Slowly, I started to wonder if my parents were right—that I should have a proper life with a proper job. My documentary had tanked, the artists were all starting to repeat themselves in the interviews, and it was time to be grown-up and have a full-time job with an official accreditation at a real Western newspaper, even if there was only so much you could say within its narrow columns. I applied for a correspondent job at one of the magazines I’d been freelancing for. The senior correspondent and an editor for the Asia desk took a look at my clips, asked a few questions about my experience, and then about my family background, as people do. I tried to paint as accurate a portrait of myself as possible, assuming they would see how lucky they were to snag a bohemian with street cred as gritty as mine. We sat at opposite ends of a long table.

The editor looked curiously at me after I’d finished talking and said, in an arch, half-joking tone, “You seem to have drifted to China and you seem to have drifted into journalism. Are you someone who drifts through life?” I felt as if he had slapped me in the face. But once I got over the initial blow, I found I enjoyed the tingle it left behind. It was proof that I had completed my transformation into a hunzi; I had killed the nerd of my teenage years. Needless to say, I didn’t get the job.

Gretchen and I were sitting around my apartment one day, talking about the wonders of our neighborhood, the chicken being raised on my stairwell, and the new fashion of wearing pajamas in public. The dot-com boom was in full swing and average, uninspired expats were coming back from New York with hundreds of thousands of dollars of venture capital that had been thrown at them over breakfast meetings. The Onion had also just started and we decided to take matters into our own hands and start our own online magazine, The Marzipan Inquirer.

Who would read the publication, you ask? Our friends, probably, both the ones who lived in Maizidian’r and the ones at home who could never quite picture our lives. And tourists. Not the rich Western tourists whom City Edition had been geared toward but the down-market tourists—Malaysians, Russians, Albanians—who stayed at the three-star New Ark Hotel in our neighborhood. I had seen them looking out the windows of their giant tour buses as they rolled down Marzipan Street, at what must have seemed a bleak landscape of blotchy socialist apartment buildings and run-down shops. I felt sorry for them, that this was their vacation. (Did they feel sorry for me, that this was my life?)

I began to write articles for our imaginary publication.

Marzipan Street Will Not Be Gentrified!: An Editorial

Interview with the Perambulator: Silent Walker Bares All in Exclusive Interview

Local Woman Wakes Neighbors with Arcane Chant, Again: “Dou! Dou! Dou! Dou!” Revealed as Name of Dog

Support Local Music: We’re Not Amateurs, Says Lead Singer Marco, That’s Just Our Band’s Name

Who needed a proper job when the Internet had the potential to make me into a publishing magnate?

• • •

&nbs

p; One day, I saw Cookie with a great new haircut.

“Pal, I just went to that gaoji salon next to Green Lake Garden,” she said. “There’s this totally wicked hairdresser there. I told her I wanted a messy haircut and she just grabbed my hair and started cutting. You know how most Chinese hairdressers take hours? She was done in fifteen minutes. I think she was trained by the French guy, Pierre or whoever.”

Green Lake Gardens was a gaoji housing complex in our neighborhood that was legal for expats to live in. We were the opposite of gaoji.

“You went to Eric’s of Paris?”

“If you don’t get your hair cut by him, it’s not expensive, maybe eighty kuai. I’m telling you, pal—go to this woman, Wang Le. She’s wicked! I mean, just look at me—aren’t I a babe?”

Eighty kuai, or ten dollars, seemed outrageously expensive for a haircut, but if she was really a genius—

“And she even does tattoos. She showed me hers!”

Eric’s of Paris was clean and sleek and full of pep, with none of the languor of a Chinese salon. Most of the customers were expats and the hairdressers spoke French as their scissors flew through hair. I was surprised by Wang Le’s appearance. Her figure looked as doughy as a tired housewife’s and her short wavy hair was tinted a light red, nothing special. A bevy of young men in black buzzed around her. Her pale, plucked, and oddly ageless face had no expression until I mentioned Cookie’s name. She lit up and immediately ordered one of her boys to give me a head massage while washing my hair, another to hand me haircutting magazines to peruse, another to bring me water to drink.

“Cookie is so huopo, isn’t she?” she said. Huopo. The word was the bane of my existence. Meaning lively and open and free, it was everything that Westerners were supposed to be and everything I did not appear to Chinese people to be. My hair was a cornerstone of this huopo problem. A bad haircut helped me blend in, which had its advantages, but then I looked like a nice Chinese girl, which stung my vanity. But if I got the flamboyant haircut I wanted, I would stick out like a ridiculous Westerner who wanted the rock-star treatment in China. I had to choose. Blend in or express myself.

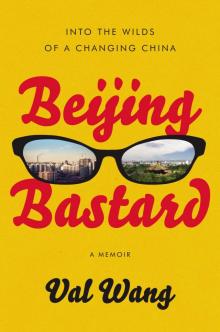

Beijing Bastard

Beijing Bastard