Beijing Bastard Read online

GOTHAM BOOKS

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Group (USA) LLC

375 Hudson Street

New York, New York 10014

USA | Canada | UK | Ireland | Australia | New Zealand | India | South Africa | China

penguin.com

A Penguin Random House Company

Copyright © 2014 by Valerie Wang

I Didn’t Understand

Words and Music by Elliott Smith

Copyright © 1998 by Universal Music—Careers and Spent Bullets Music

All Rights Administered by Universal Music—Careers

International Copyright Secured All Rights Reserved

Reprinted by Permission of Hal Leonard Corporation

Penguin supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin to continue to publish books for every reader.

Gotham Books and the skyscraper logo are trademarks of Penguin Group (USA) LLC.

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

has been applied for.

ISBN 978-0-698-15699-9

While the author has made every effort to provide accurate telephone numbers, Internet addresses, and other contact information at the time of publication, neither the publisher nor the author assumes any responsibility for errors or for changes that occur after publication. Further, the publisher does not have any control over and does not assume any responsibility for author or third-party websites or their content.

Penguin is committed to publishing works of quality and integrity. In that spirit, we are proud to offer this book to our readers; however, the story, the experiences, and the words are the author’s alone.

For my family

Contents

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Epigraph

Part One

Chapter One: I H_T_ CH_N_S_ SCH_ _ L

Chapter Two: Fresh Tensions in U.S.–China Relations

Chapter Three: Like Extras Late for a Take

Chapter Four: Then There Is the Urination

Chapter Five: Miss, You’re Not a Beijinger, Are You?

Part Two

Chapter Six: The Original Beijing Bastard

Chapter Seven: Harbinger, Harbinger, Harbinger

Chapter Eight: The Most Important Man in My Story

Chapter Nine: The Redemptive Power of Family

Chapter Ten: Seeks Trouble for Oneself

Part Three

Chapter Eleven: It Stinks

Chapter Twelve: Yijia’s Grand Opening

Chapter Thirteen: Peking Man

Chapter Fourteen: To Fill In the Blanks

Chapter Fifteen: Young Woman, Old Men

Chapter Sixteen: The Evening Swan

Chapter Seventeen: Peking Opera & Sons

Part Four

Chapter Eighteen: Fifty Years Later

Chapter Nineteen: The Warrior and the Clown

Chapter Twenty: To Know Your Own Life

Chapter Twenty-one: The Decomposing Heart of Old Beijing

Chapter Twenty-two: Facts Are Facts

Part Five

Chapter Twenty-three: The Marzipan Inquirer

Chapter Twenty-four: Topless Subtitling

Chapter Twenty-five: The Outlaws Are the Ones Who Become Moral

Chapter Twenty-six: Not Really “In the Mood for Love”

Chapter Twenty-seven: In the Path of the Wrecking Ball

Part Six

Chapter Twenty-eight: The Shade Provided by the Branches Is Gone

Chapter Twenty-nine: I Hope to Bring This Tape to You in Person

Chapter Thirty: Your Face Is So Magnificent, but the Back of Your Head Has Rotted Away

Chapter Thirty-one: Qu Qu’r in America

Epilogue

Acknowledgments

You take delight not in a city’s seven or seventy wonders but in the answers it gives to a question of yours.

—Italo Calvino, Invisible Cities

Part One

Chapter One

I H_T_ CH_N_S_ SCH_ _ L

On the very first page of a book about Christopher Columbus that my dad is reading to me, there is a word I don’t know. I am squeezed next to him in the creaky maroon recliner where he does all his reading. Every new word opens up new worlds to me. This one has a long, slow sound to it and looks so different than it sounds.

“What is a journey?” I ask. He looks surprised and pauses before answering.

“A journey is a long trip,” he says.

“A long trip!” What a disappointment. But as we read further into the book, I see what he means. A trip is what happens when I go with my mom to the store, or when we visit my grandparents in Virginia, five hours away. But a journey is when you sail into uncharted waters searching for something you’ve seen with only your innermost eye. You cross perilous seas, lose half your crew to scurvy, and discover a place that will later be called America.

I’m not sure why this memory etched itself so deeply into my mind. Maybe I was starting to realize that my parents had made a journey like that years before. Maybe my dad had even told me that he too had come to America on a boat.

My parents had both been born in China in the early 1940s and just before the Communist takeover in 1949 had both fled with their families to Southeast Asia. Before the age of eighteen, they had immigrated separately to New York, where they met and married. They moved to Washington, D.C., in the late 1960s, and then months before my older brother was born in 1973, they moved to a beige colonial with brown shutters on a cul-de-sac in the D.C. suburbs, where I grew up and where they still live today. Throughout my childhood in the 1980s, as China opened up to the world, my parents promised we would visit the motherland when I turned thirteen.

They bought the suburban house and quarter-acre lot when it was no more than an empty field; the area had been farmland just years before. Our house had no past, only a future, and perhaps that’s how they wished to see their lives too. You can be anything you want to be in life, my mom always told us.

When asked in second grade to draw a picture of what I wanted to be when I grew up, I drew myself sitting by a sunny window, my fingers on the keys of a typewriter.

Shortly after moving into their new house, my parents planted twenty-nine white pine trees around the perimeter of the bare yard to separate the house from the identical houses around it, the saplings so tiny that my then-tiny brother accidentally trampled one to death, so the story goes. For years my parents had lived in small homes filled with too many people, and planting the pine trees was a grandiose gesture marking out the kingdom where they hoped to live happily ever after. Over the next twenty or so years, the pine trees grew taller than the house, shielding our yard from the sun and the neighbors. “Good fences make good neighbors,” declared my dad once. We were each proud in our own way of the dark line of trees. I liked the feeling they gave me that I was growing up in a forest.

The suburbs allowed my parents to create for the first time an orderly world that they had total control over. The rhythms of our yard ran like clockwork. The forsythias were the first to bloom in the spring, then the three dogwood trees in the front and the petite red maple tree in the back. Summer brought perfect, perfumed roses, and sugar snap

peas and tomatoes from the vegetable garden, and many empty hours for me to spend alone under the sheltering cave of the forsythia bushes, a space too small for adults. A big chive patch grew all year round. Cardinals and blue jays came regularly to the pine trees. While other families around us hired gardeners and landscapers, my parents tended the yard by themselves. My dad trimmed the hedges and aerated the lawn with a machine that made the rounds among the Chinese families in our area. My mom mowed and watered the lawn and put herself in charge of patrolling its borders. When rabbits began ravaging her vegetable garden, she chased down a marauding baby bunny and trapped it under a pail, oblivious to its mother’s screams, and let it go by a nearby creek. (“Who should be eating the crunchy snow peas—the rabbit’s baby or my baby?” she asked.) Hornets stung my allergic dad, and so she swaddled herself head to toe in protective outerwear, ripped their nest from its moorings, and threw it out with the evening’s trash. Once when mowing the lawn, she spotted a snake in the grass. My brother and I ran over to see, and he, with a vast storehouse of knowledge gleaned from the World Book, declared it to be a common, harmless garter snake. “Oh, a garden snake,” she said, and ran it over with the lawnmower. It was not wise to cross my mother.

My mom peppered my childhood with stories of her own childhood so fantastical and vivid I felt as if I’d experienced them firsthand. She remembered only snapshots from her early childhood in China: the frightening smell from her grandfather’s long opium pipe, the grand car that chauffeured her to kindergarten, the huge house built with money from the jade and timber trades. When she was four, in 1949, a cargo truck smuggled her and her family out of China in the middle of the night; she remembers struggling to keep her younger siblings quiet in the back. They carried nothing of value but the jade jewelry sewn into her mother’s belt. Her parents, having never worked a day in their lives, ran a teahouse called Airplane in Shwebo, Burma, as they raised seven children in a two-room house. Burma seemed even wilder than China: Poisonous snakes slithered free in the streets, green mangoes grew in her family’s backyard and were eaten sour and sprinkled with salt, an annual water-splashing festival took over the streets of the city.

For high school, my mom went to a Chinese boarding school an overnight train ride away in Rangoon. When she was a senior, a mysterious man called her, saying he was a friend of her uncle’s in America and asking her to meet him at a hotel, a nice hotel. Her uncle had left to study in America in the 1930s before she was born and when war broke out in China, his father had told him not to return. He had lost contact with his family in China and had heard only that they had fled to Burma, so when he found out his friend was going to Rangoon on business, he asked him to track them down. The man gave my mom her uncle’s address in New York as well as a gift from him, a small Gruen watch. She wrote him a letter, and several months later she flew to New York alone to live with his family. On cold winter mornings, while waiting for the city bus to take her to Queens College, she would buy a single bagel from the shop by the bus stop and hold it in her hands to warm them. Her parents and six younger siblings didn’t immigrate to the States until a decade later.

Her stories opened up amazing, faraway worlds that seemed a part of mine, even if they couldn’t have been more distant.

Many other Chinese immigrants had also moved to the D.C. area, and it allowed my parents to administer to my brother and me a nearly lethal dose of “Chinese” culture. As regular as church, we attended Chinese School every Sunday, from the first week of kindergarten to the last of high school, learning Mandarin Chinese. Potomac Chinese School was held in the rented classrooms of Herbert Hoover Junior High School, with my mom and other parents working as teachers doling out homework, tests, and report cards and ranking us as they had been ranked growing up.

On one test, I wrote I H_T_ CH_N_S_ SCH_ _L, Wheel of Fortune–style, and the teacher filled in the missing vowels.

I also performed in a Chinese dancing troupe whose signature piece, performed at the Kennedy Center and the National Theatre as well as at a random crab house off the interstate, was a lyrical evocation of tea harvesting, in which we plucked invisible tea leaves off of imaginary vines and delicately placed them into real straw baskets, in between sequences of trotting in a line, pausing, snapping open and closed sequined pink silk fans, and then trotting again. When our bookings fell in direct proportion to the waning of our cuteness, I immediately switched to karate, which my brother was already learning, and eight years and eleven broken boards later, I was a black belt. Of course I took piano lessons too, de rigueur for a proper suburban Chinese-American upbringing, and took tennis lessons because my parents had heard that the tennis court was where all the real deals got made in America.

Growing up, we spent a lot of time with my dad’s extended family, a rigidly hierarchical Confucian family headed by Yeye, my grandfather. He was a classic patriarch—arrogant, overbearing, awe-inspiring, never attired in less than a three-piece suit and hat. When I saw Ayatollah Khomeini on TV thundering angrily at masses of people, I mistook him for Yeye, just doing his day job as a history professor. Yeye made no secret of the fact that he liked my brother more because he would carry on the family name. (My mom, on the other hand, made a point of treating us equally.) My brother, as the Number One Son of the Number One Son, bore a heavy burden to live up to the values exemplified by Yeye: hard work, integrity, filial obligation. I, as the youngest of the clan, felt pulled in two directions: Of course I wanted to measure up but I also wanted to poke fun at their pious values and disrupt their precious order. Youngest siblings are natural contrarians; subverting the rules of the family is one of the few ways we can wield power.

Yeye would always demand I answer the same question: “Are you Chinese or American?” I thought it a silly choice, but because I knew he wanted me to say Chinese, I always said American.

China seemed impossibly distant. Yeye had been born in Hunan, like Chairman Mao, but instead of becoming a Communist became an ardent Nationalist. He had studied his way out of the provinces, first to a top university in Beijing, then abroad in the 1920s, earning a doctorate in comparative government from Columbia University. He returned to China in the 1930s to help build the new nation. Once when visiting Shanghai, he was invited to dinner by a friend and his wife, who brought along her younger sister to accompany him. Smitten, he invited the three of them out for dinner again the next night. After the young woman returned home to Beijing, he followed a few days later to ask her father for her hand in marriage. They married, bore three children, and, after moving around the country with the Nationalists, returned to Beijing and bought a courtyard house in 1946. Then just before the Communists took over in 1949, the family fled, first to Hong Kong briefly, then Jakarta, Indonesia, for almost a decade, where Yeye edited The Free Press, a Chinese newspaper. In the late 1950s, he moved the family to the States, leaving them on the Upper West Side of New York while he taught at universities around the country. Nainai took the English name Lily. Her older sister, who went by Mabel, made it to the States via Macau and also ended up on the Upper West Side, several blocks away. She too had left behind a courtyard house in Beijing.

Yeye eventually found a position in the history department of Hampton University. Every Easter and summer vacation, we went to visit them in their little green bungalow in Hampton. Nainai always had a box of fresh brownies ready, crisp on the top, tender inside. For Christmas, they came to our house, and as Nainai lay on the guestroom bed reading the Chinese newspaper, I would climb in with her and point out all the familiar characters that jumped out at me from the gray blur of stories. She would sing me Chinese songs in an exaggerated, old-timey voice that made me laugh. But she also had a sternness that intimidated me. When I was six and out with her alone, I was too scared to ask to go to the bathroom and ended up soaking the faux sheepskin lining of my boots.

Yeye had constant conflicts with my parents about what language to speak to us at home. He lecture

d us about using “ear training” to learn Chinese, while my parents spoke English to us out of fear that otherwise we would fall behind in school. They spoke mostly Chinese with each other. I am embarrassed to say I mocked Yeye’s accent, parroting his “eaah training.”

Though my family had succeeded in making a life in the States, I always wondered about China. Poems and myths I read in Chinese School implanted in a secret compartment of my mind hazy images: a boat on a lake at dusk . . . a festival . . . I was there, lighting paper lanterns and setting them afloat on the lake . . . ghosts of drowned women rising from the water . . . My family also watched National Geographic specials about China together; I was haunted by an image of a live monkey’s head held in a vise, cracked open like a coconut and its brains scooped out and eaten fresh as a roadside snack. The romantic and the ghoulish mixed into a potent brew in my mind and I was eager to see this place in person. I imagined that it would be like visiting a large museum of ancient civilization that would cleanly elucidate some deep truths about my family. I was thirteen in the summer of 1989; after the Tiananmen Square Massacre, my parents never spoke again about visiting China.

It was during my teenage years that my relationship with my parents fell apart. I found the hermetically sealed environment of our suburban home suffocating, my go-go Chinese-American lifestyle of nonstop studying unbearable, my parents ceaselessly dictatorial. The community I’d grown up in was stifling—everyone knew whose children went to Harvard and whose got pregnant, whose families were getting ahead in America and whose were falling behind. My successes or failures were theirs as well, and nothing was ever enough for them. It turned out that we could be anything we wanted to be in life—as long as it was a doctor or a lawyer. My older brother followed all the rules; he got into an Ivy League college and would go on to be a lawyer, support Republican tax cuts, and never date. For a while I copied him exactly. I earned my black belt, attended a math and science magnet school, became the editor of my high school newspaper. Though I mimed the right actions, my heart wasn’t in it. All I knew was the simple urge to do the opposite of what I was supposed to do: date white boys, talk nonstop on the phone, agitate for a driver’s license. I idolized Georgia O’Keeffe and had a crush on Andre Agassi and imagined myself their lovechild: an ascetic, passionate being trying to break free from the repression of the East Coast and a world where deals were made on the tennis court.

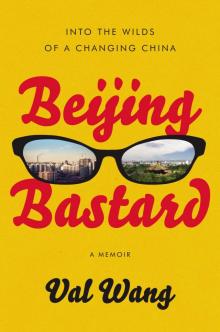

Beijing Bastard

Beijing Bastard